YBCO-

A High-Temperature superconductor (HTS)

Superconductors have long been the field of research for physicists and engineers due to their unique ability to conduct electricity with zero resistance. Among the most celebrated breakthroughs in this field is Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide (YBCO) — a high-temperature superconductor (HTS) discovered in 1987. It marked the first material to exhibit superconductivity above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen (77 K), revolutionizing the feasibility of practical superconducting technologies.

Table of Contents

What is YBCO?

YBCO stands for Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide, with the general formula:

YBa₂Cu₃O₇₋ₓ, where x ranges between 0 and 1. This compound belongs to the family of cuprate superconductors and is characterized by layered perovskite structures

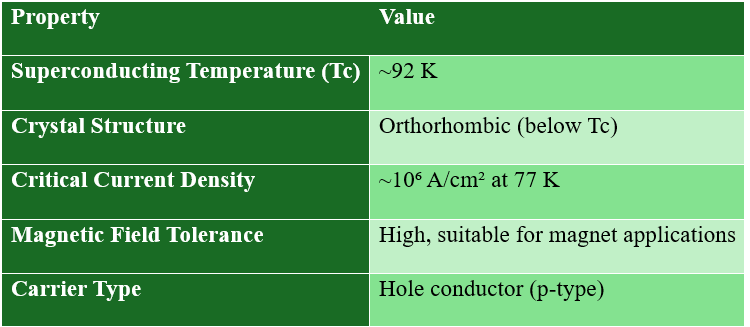

Key Properties of YBCO:

Structural Analysis of YBCO: Linking Atomic Arrangement to Superconducting Behaviour

The crystal structure of Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide (YBa₂Cu₃O₇–δ), commonly called YBCO, is a layered perovskite-derived compound, built from alternating sheets of CuO chains, CuO₂ planes, BaO layers, and Yttrium atomic layers, stacked along the crystallographic c-axis. The first figure illustrates this layered sequence clearly: the CuO₂ planes serve as the superconducting layers, where Cooper pairs form and carry current without resistance, while the CuO chains act as charge reservoirs, supplying holes to the CuO₂ planes and tuning their electronic properties. Between these conducting layers lie BaO layers (which contain apical oxygens connecting planes and chains) and a Y³⁺ layer, which separates the double CuO₂ planes and controls their coupling. The structural symmetry, typically orthorhombic in oxygen-rich compositions (δ ≈ 0–0.1), arises from ordered oxygen atoms in the CuO chains, while removal or disordering of these oxygen atoms (δ > 0.5) leads to a tetragonal phase with equal lattice parameters a = b.

Each of these layers has a distinct role:

- CuO chains (Cu(1) sites) → Charge reservoir: Control hole doping into the CuO₂ planes.

- BaO layers → Provide spacing and hold apical oxygens (O(4)) that bridge chain and plane copper atoms.

- CuO₂ planes (Cu(2) sites) → Superconducting layers: Where Cooper pairs form and carry current.

Y³⁺ layer → Acts as a spacer between the two CuO₂ planes, maintaining the layered structure

Colour and Symbol Representation:

Symbol | Meaning | Role |

Dark teal large circles (Y³⁺) | Yttrium atoms | Sits between CuO₂ planes |

Medium teal circles (Cu²⁺/Cu²⁺⁺) | Copper atoms | Two distinct sites: Cu(1) in chains, Cu(2) in planes |

Small teal/light blue circles (Oxygen atoms) | O(1)–O(3) oxygens | Occupy planar, chain, and apical positions |

Oxygen Sub-lattice (O(1), O(2), O(3))

The oxygen atoms are the key to understanding orthorhombicity and superconductivity.

- O(1) → Located in CuO chain layer, runs along the b-axis.

- These form continuous Cu–O–Cu chains when fully occupied (oxygen-rich, orthorhombic phase).

- Oxygen vacancies here (when δ ↑) destroy the chains and reduce hole doping.

- O(2) and O(3) → In the CuO₂ planes, forming the CuO₄ square networks.

- These oxygens are tightly bound and define the superconducting planes.

- O(4) (not always labeled but implicit in the BaO layer) → Apical oxygen, connects Cu in the planes to the BaO layers and indirectly to the CuO chains.

YBCO exhibits two distinct structural forms — orthorhombic and tetragonal — each closely linked to its oxygen content and superconducting behavior. In the orthorhombic phase, the oxygen atoms in the CuO chain layer are well ordered, forming continuous Cu–O–Cu chains that enable efficient hole transfer to the CuO₂ planes. This charge transfer mechanism results in optimal doping of the superconducting planes, giving rise to high-temperature superconductivity with a critical temperature around 92 K.

In contrast, when oxygen is partially removed or becomes disordered, the CuO chains break, leading to a tetragonal structure in which the a and b lattice parameters become equal. This disruption reduces hole concentration in the CuO₂ planes, suppressing superconductivity entirely. Thus, the transition from orthorhombic to tetragonal symmetry reflects not just a structural change but also a fundamental shift in electronic behavior, governed by the degree of oxygen ordering within the lattice.

Orthorhombic vs. Tetragonal Nature

- In the figure, the CuO chain layer appears ordered and continuous, implying an oxygen-rich, orthorhombic YBCO (δ ≈ 0–0.1).

- When O(1) sites become partially empty (δ ≈ 0.6), the structure transitions to tetragonal (a = b).

- The orthorhombic distortion (b > a) arises from these filled chains along b.

Functional Role of Each Layer:

Layer | Function | Atomic Components | Physical Effect |

CuO chains | Charge reservoir | Cu(1) + O(1) | Dopes holes into CuO₂ planes |

BaO layer | Structural + apical bridge | Ba + O(4) | Provides apical O, connects planes and chains |

CuO₂ plane | Superconducting | Cu(2) + O(2,3) | Supports Cooper pair formation |

Y layer | Spacer | Y³⁺ | Controls inter-plane coupling |

Along the c-Axis (Marked with Arrow “c”)

The arrow labeled “c” shows the crystallographic c-axis direction, along which these layers repeat periodically.

The c-axis lattice constant ≈ 11.68 Å in the oxygen-rich form.

Each full stack from one CuO chain to the next defines one unit cell height.

The figure compares the two structural states — orthorhombic (superconducting) and tetragonal (non-superconducting) YBCO.

In the orthorhombic phase, the O(1) atoms are well ordered along the Cu(1) chains, creating continuous Cu–O–Cu pathways that maintain high oxygen content and strong hole doping into the CuO₂ planes. This ordered arrangement induces a slight asymmetry between the a and b axes (b > a), stabilizing the orthorhombic distortion and enabling a critical temperature (Tc) of about 92 K. In contrast, the tetragonal phase results when the CuO chain oxygens (O(1)) become vacant or disordered, breaking the chain continuity. As a result, the structure loses orthorhombicity, the CuO₂ planes become underdoped, and superconductivity is suppressed. The inset diagrams of the Cu(1) chain and CuO₂ plane further help visualize this: the ordered Cu–O–Cu chains are crucial for transferring charge to the superconducting planes.

Overall, YBCO’s exceptional superconducting behavior arises from the delicate interplay between structural order and oxygen stoichiometry. The orthorhombic–tetragonal transition, as shown in the figures, is not merely a change in symmetry but a direct reflection of how the oxygen sub-lattice dictates electronic structure and superconducting properties. For nanoceramic YBCO, maintaining this chain oxygen order across nanosized grains and grain boundaries is essential for preserving its high Tc and electrical connectivity. Hence, a deep understanding of its atomic-scale structure, as visualized in these diagrams, is fundamental for students and researchers studying high-temperature superconductivity and advanced oxide materials.

The figure provides a concise yet powerful understanding of the crystal architecture and functional mechanism of YBa₂Cu₃O₇–δ (YBCO). It shows that YBCO is built from alternating layers of CuO chains and CuO₂ planes, which together form the foundation of its superconducting structure. The CuO₂ planes are the active superconducting regions where electrical conduction occurs without resistance, while the CuO chains act as charge reservoirs that regulate the electronic state of these planes. This layered design is what makes YBCO a high-temperature superconductor with remarkable anisotropic properties.

A critical factor illustrated in the figure is oxygen ordering, especially the distribution of O(1) atoms in the CuO chains. These oxygen atoms control the symmetry of the crystal — ordered chains lead to an orthorhombic structure and optimal superconductivity, while disordered or deficient oxygen results in a tetragonal structure and loss of superconductivity. The charge transfer mechanism operates through these layers: holes (positive charge carriers) move from the CuO chains, through the BaO layers, into the CuO₂ planes, enabling superconductivity. The yttrium layer, positioned between two CuO₂ planes, acts as a structural separator that maintains spacing and gives rise to anisotropic three-dimensional connectivity, meaning the material conducts better in-plane than along the c-axis.

For nanoceramic YBCO, this structural control becomes even more vital. At the nanoscale, grain boundaries and oxygen deficiency can disrupt the continuity of CuO chains and the uniformity of hole doping, leading to reduced superconducting performance. Therefore, precise oxygen control and well-engineered grain-boundary structures are essential for preserving the high critical temperature (Tc ≈ 92 K) and robust superconducting pathways. In essence, the figure teaches that YBCO’s extraordinary properties arise from the synergy between structure, oxygen ordering, and charge dynamics, all of which must be maintained to achieve high-Tc superconductivity in both bulk and nanoceramic forms.

Structure and Superconductivity Mechanism

YBCO consists of CuO₂ planes, which are primarily responsible for superconductivity. These planes are separated by layers containing yttrium and barium atoms. The superconducting behaviour arises due to Cooper pairing of electrons (or holes), facilitated by lattice vibrations (phonons) and magnetic interactions — although the exact mechanism in cuprates is still debated.

Oxygen Content and Superconductivity

The value of x in YBa₂Cu₃O7-x determines the oxygen stoichiometry, directly affecting the superconducting transition temperature (Tc). Full oxygenation (x ≈ 0) gives optimal Tc (~92 K), while oxygen deficiency can destroy superconductivity.

Synthesis and Fabrication Techniques

- Solid-State Reaction: Mixing Y₂O₃, BaCO₃, and CuO, followed by calcination and sintering.

- Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD): Used to fabricate YBCO thin films with precise crystalline orientation, especially for electronics.

- Metal Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition (MOCVD): Preferred for large-scale coated conductors.

Challenges in Fabrication:

- Maintaining oxygen stoichiometry

- Achieving epitaxial growth

- Avoiding secondary phase formation (e.g., BaCuO₂)

YBCO stands as a cornerstone in the field of high-temperature superconductivity. With its critical transition temperature above 77 K and wide-ranging applications from quantum devices to power grids, it remains a focus of both fundamental research and industrial innovation. Despite its challenges, continuous advancements in synthesis and nanostructuring are paving the way for scalable and sustainable superconducting technologies.

References

Bednorz, J. G., & Müller, K. A. (1986). Possible high-Tc superconductivity in the Ba–La–Cu–O system. Zeitschrift für Physik B Condensed Matter, 64(2), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01303701

Wu, M. K., Ashburn, J. R., Torng, C. J., Hor, P. H., Meng, R. L., Gao, L., Huang, Z. J., Wang, Y. Q., & Chu, C. W. (1987). Superconductivity at 93 K in a new mixed-phase Y–Ba–Cu–O compound system at ambient pressure. Physical Review Letters, 58(9), 908–910. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.908

Cava, R. J., Batlogg, B., van Dover, R. B., Murphy, D. W., Sunshine, S. A., Siegrist, T., Remeika, J. P., Rietman, E. A., Zahurak, S. M., & Espinosa, G. P. (1987). Bulk superconductivity at 91 K in single-phase oxygen-deficient perovskite Ba₂YCu₃O₉–δ. Physical Review Letters, 58(16), 1676–1679. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.1676

Jorgensen, J. D., Veal, B. W., Paulikas, A. P., Nowicki, L. J., Crabtree, G. W., Claus, H., & Kwok, W. K. (1990). Structural properties of oxygen-deficient YBa₂Cu₃O₇–δ. Physical Review B, 41(4), 1863–1877. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.41.1863

Orenstein, J., & Millis, A. J. (2000). Advances in the physics of high-temperature superconductivity. Science, 288(5465), 468–474. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.288.5465.468

Tallon, J. L., & Loram, J. W. (2001). The doping dependence of T₍c₎ in high-Tc cuprates. Physica C: Superconductivity, 349(1–2), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-4534(00)01524-0

Piriou, A., Jenkins, N., Berthod, C., Maggio-Aprile, I., & Fischer, Ø. (2008). First direct observation of the CuO chains contribution to superconductivity in YBa₂Cu₃O₇–δ by scanning tunneling spectroscopy. Nature Physics, 4(8), 503–508. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys962

Pickett, W. E. (1989). Electronic structure of the high-temperature oxide superconductors. Reviews of Modern Physics, 61(2), 433–512. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.61.433

Veal, B. W., Paulikas, A. P., & Jorgensen, J. D. (1990). Oxygen ordering and superconductivity in YBa₂Cu₃O₆+x. Physical Review B, 42(9), 6305–6316. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.42.6305

Poole, C. P., Farach, H. A., Creswick, R. J., & Prozorov, R. (2014). Superconductivity (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN: 978-0-12-409502-7

Koblischka, M. R., & Murakami, M. (2000). Flux pinning and the development of high-Tc superconductors. Superconductor Science and Technology, 13(5), 738–753. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/13/5/318

Wang, X., Wang, S., Li, Y., & Zhao, J. (2017). Enhanced superconducting properties in YBCO nanoceramics prepared via sol–gel route. Ceramics International, 43(18), 16614–16621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.09.122

Dr. Rolly Verma

Explore More from Advance Materials Lab

Deepen your insight into material behavior with expert resources on advanced materials crafted to support research scholars and advanced learners. Each guide is designed for research scholars and advanced learners seeking clarity, precision, and depth in the field of materials science and nanotechnology.

🔗 Recommended Reads and Resources:

Ferroelectrics Tutorials and Research Guides — Comprehensive tutorials covering polarization, hysteresis, and ferroelectric device characterization.

Workshops on Ferroelectrics (2025–2027) — Upcoming training sessions and research-oriented workshops for hands-on learning.

Glossary — Ferroelectrics and Phase Transitions — Concise explanations of key terminologies to support your study and research work.

- Blogs — Insightful articles across science, technology, education, and academic career development.

If you notice any inaccuracies or have constructive suggestions to improve the content, I welcome your feedback. It helps maintain the quality and clarity of this educational resource. You can reach me at: advancematerialslab27@gmail.com