Carbon Nanotubes - Part 1: Discovery and Growth Mechanisms

In the world of nanotechnology, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) stand out as one of the most iconic and influential nanomaterials. Their unique one-dimensional structure, extraordinary physical properties, and wide range of applications have made them a central topic in both academic research and advanced technological development. However, the scientific importance of CNTs goes far beyond their applications. Understanding when and how carbon nanotubes were discovered provides valuable insight into how modern nanoscience evolved and how careful experimental observation can lead to revolutionary breakthroughs. This historical perspective helps students appreciate CNTs not merely as advanced materials, but as a milestone in the development of nanoscale science and engineering.

Scientific Background Before the Discovery of Carbon Nanotubes

Before carbon nanotubes were formally identified, scientists already knew that carbon is an exceptionally versatile element. A single carbon atom can bond with other carbon atoms in different ways, giving rise to multiple structural forms known as allotropes. For centuries, diamond and graphite were the most familiar allotropes of carbon. Diamond is a three-dimensional network in which each carbon atom forms four strong covalent bonds, resulting in extreme hardness. Graphite, on the other hand, consists of two-dimensional layers of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal pattern, where each atom bonds with three neighbors. These layers, later called graphene sheets, are held together by weak van der Waals forces, allowing them to slide easily over one another.

As experimental techniques advanced in the late twentieth century, particularly electron microscopy and vacuum-based synthesis methods, researchers began exploring carbon structures at much smaller length scales. During studies on carbon soot, vapor-grown carbon fibers, and arc-discharge products, unusual filament-like and tubular carbon structures were occasionally observed. At the time, these features were often dismissed as defects or by-products rather than recognized as a new class of materials. The scientific community had not yet developed the conceptual framework or the analytical tools needed to fully understand and classify such nanoscale carbon forms.

This situation began to change dramatically in the 1980s with the discovery of closed-cage carbon molecules known as fullerenes. The realization that carbon atoms could organize themselves into stable, hollow nanostructures challenged traditional views of carbon chemistry. This breakthrough opened the door to the idea that carbon might also form other low-dimensional structures beyond flat layers and spherical cages. It was within this evolving scientific atmosphere—where curiosity about carbon at the nanoscale was rapidly growing—that the stage was set for the discovery of carbon nanotubes.

Accidental Discovery of Carbon Nanotubes (1991)

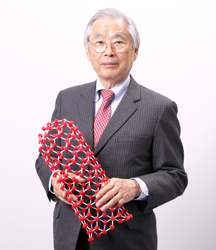

The formal discovery of carbon nanotubes occurred in 1991, through the meticulous work of Sumio Iijima. At that time, Iijima was not actively searching for a new nanomaterial. Instead, he was investigating carbon soot produced during arc-discharge experiments, a technique primarily used to synthesize fullerenes.

In a typical arc-discharge process, a high electric current is passed between two graphite electrodes in an inert atmosphere. This intense electrical arc vaporizes carbon atoms, which then cool and condense into various carbon structures. Researchers expected mainly spherical fullerene molecules and amorphous carbon to form in the resulting soot.

When Iijima examined this soot using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), he observed something completely unexpected. Embedded within the carbon deposits were long, hollow, cylindrical structures composed of concentric layers of carbon. These tubes had diameters on the order of a few nanometers, yet their lengths extended to several micrometers—an aspect ratio never seen before in carbon materials.

Closer atomic-scale analysis revealed that these tubes were not solid fibers. Instead, they consisted of graphene sheets seamlessly rolled into cylindrical shapes, with carbon atoms arranged in a highly ordered hexagonal lattice. Many of the structures contained multiple concentric shells, later termed multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs).

What made this observation truly groundbreaking was not only the unusual shape of these structures, but also the clarity with which their atomic arrangement was identified. For the first time, carbon was shown to naturally form a stable, one-dimensional nanostructure with near-perfect crystallinity. Iijima carefully documented these findings and published them in Nature in 1991, a paper that immediately attracted global attention and marked the beginning of modern carbon nanotube research.

This discovery illustrates an important lesson for students of materials science: major scientific breakthroughs often arise from careful observation rather than deliberate searching. Carbon nanotubes existed within carbon soot for years, but it required advanced microscopy, patience, and scientific insight to recognize them as a new and fundamentally important form of matter.

Why Carbon Nanotubes Were Not Recognized Earlier (Despite Prior Observations)

Although carbon nanotube–like structures were observed decades before 1991, they were not recognized as a distinct and revolutionary material system. This delay was not due to a lack of scientific effort, but rather a combination of technological and conceptual limitations.

First, advanced characterization tools were not widely available. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), capable of resolving atomic-scale lattice structures, became reliable only in the late 1980s. Earlier electron microscopes could reveal filamentary or tubular shapes, but they lacked the resolution needed to clearly identify the hexagonal graphene lattice and the hollow, concentric-shell structure that defines carbon nanotubes. Without atomic-level clarity, these structures were often interpreted as defective carbon fibers or irregular soot particles.

Second, the scientific framework for low-dimensional materials did not yet exist. Before the discovery of fullerenes, the idea that carbon atoms could self-assemble into stable, hollow nanostructures was not widely accepted. Graphene itself had not yet been isolated or formally recognized as a standalone material. As a result, even when tubular carbon features were observed, researchers lacked the theoretical language and conceptual models to classify them as a new allotrope of carbon.

Third, research focus and priorities were different. Many early observations occurred during studies on carbon black, combustion products, or vapor-grown carbon fibers. In these contexts, tubular structures were seen as by-products rather than as objects of primary interest. Since the goal of those studies was not nanomaterial discovery, the unusual morphologies were often noted briefly and not investigated in depth.

Finally, scientific visibility played a crucial role. Earlier reports, including those published in the 1950s and 1970s, appeared in less widely circulated journals and lacked detailed structural interpretation. In contrast, the 1991 publication by Sumio Iijima combined high-quality experimental evidence with clear atomic-scale explanation and global dissemination, allowing the scientific community to immediately recognize the significance of the findings.

How CNT Discovery Changed Nanoscience and Materials Research

The discovery of carbon nanotubes marked a turning point in modern nanoscience. For the first time, researchers had access to a material that was truly one-dimensional, with a diameter on the nanometer scale and a length extending into the micrometer range. This unique geometry enabled scientists to explore physical phenomena that occur when electrons, phonons, and mechanical stress are confined to nearly one dimension.

From a materials science perspective, CNTs demonstrated that extraordinary properties can emerge purely from atomic arrangement and dimensionality, even when the chemical composition remains the same. Carbon nanotubes showed exceptional mechanical strength, high electrical conductivity (metallic or semiconducting depending on structure), and remarkable thermal stability. These discoveries challenged traditional material design principles, which had previously focused mainly on composition rather than structure at the nanoscale.

The impact of CNT discovery also extended beyond physics and materials science. It catalyzed rapid growth in nanotechnology as an interdisciplinary field, linking chemistry, electronics, mechanical engineering, and biotechnology. CNTs became model systems for studying quantum transport, nanoscale mechanics, and surface-dominated phenomena. Moreover, their discovery directly inspired the isolation of graphene and accelerated research into other low-dimensional materials such as nanowires and two-dimensional crystals.

Most importantly, carbon nanotubes changed how scientists think about materials themselves. They reinforced the idea that new functional materials can be discovered by revisiting familiar elements under new length scales and with new tools. This shift in perspective continues to influence modern research in nanomaterials, energy devices, sensors, and nanoelectronics.

Practical Applications of Carbon Nanotubes in Today’s Technology

Since their discovery, carbon nanotubes have moved steadily from laboratory curiosity to real-world technological relevance. Their exceptional combination of mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, thermal stability, and nanoscale dimensions makes them suitable for applications that conventional materials struggle to achieve.

In electronics and nanoelectronics, CNTs are explored as channel materials for next-generation transistors. Unlike silicon, carbon nanotubes can carry very high current densities with minimal heat generation. Semiconducting CNTs are being investigated for low-power, high-speed field-effect transistors, while metallic CNTs are considered for nanoscale interconnects where traditional copper wiring faces scaling limitations.

In the field of composite materials, CNTs are already making a measurable impact. Even a small addition of CNTs to polymers, ceramics, or metals can dramatically enhance mechanical strength, stiffness, and fatigue resistance. These CNT-reinforced composites are used in aerospace components, sports equipment, protective coatings, and lightweight structural parts, where strength-to-weight ratio is critical.

CNTs also play a significant role in sensing technologies. Due to their extremely high surface-to-volume ratio, carbon nanotubes are highly sensitive to changes in their surrounding environment. This makes them ideal for gas sensors, chemical sensors, and biosensors capable of detecting minute concentrations of molecules. CNT-based sensors are being explored for environmental monitoring, medical diagnostics, and industrial safety systems.

In energy-related applications, carbon nanotubes are used in electrodes for lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors to improve charge transport and cycling stability. Their high electrical conductivity and large surface area also make them attractive for fuel cells and flexible energy storage devices, supporting the global push toward sustainable and portable energy solutions.

In biomedical and healthcare technologies, CNTs are investigated for drug delivery, bioimaging, and tissue engineering. Their nanoscale size allows them to interact with biological systems at the cellular level. While challenges related to biocompatibility and safety remain, controlled and functionalized CNTs show promise in targeted therapy and advanced diagnostic tools.

Futuristic Outlook: Where CNT Technology Is Headed

Looking ahead, carbon nanotubes are expected to play a transformational role in future technologies. As device dimensions continue to shrink, CNTs offer a pathway beyond the physical limits of traditional materials. One major futuristic direction is carbon-based electronics, where CNTs and graphene could gradually complement or replace silicon in specific high-performance and low-power applications.

CNTs are also central to the development of flexible and wearable electronics. Their ability to maintain electrical conductivity under bending and stretching makes them ideal for foldable displays, electronic textiles, and implantable medical devices. This flexibility opens doors to technologies that integrate seamlessly with the human body and everyday life.

Another promising frontier is quantum and nanoscale transport devices, where CNTs act as near-ideal one-dimensional systems. These structures allow researchers to study quantum effects directly and may contribute to future quantum computing, nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS), and ultra-sensitive detectors.

From a materials design perspective, CNTs are guiding the future of smart and multifunctional materials—systems that combine mechanical strength, electrical response, and sensing capability in a single platform. Such materials could revolutionize infrastructure monitoring, aerospace safety, and autonomous systems.

Final Takeaways — Part 1 of the CNT Series

To conclude Part 1: Discovery and Growth of Carbon Nanotubes, a few key points are worth emphasizing for students and researchers:

- Carbon nanotubes were not an accidental novelty, but the result of carbon’s unique bonding ability revealed at the nanoscale.

- Their delayed recognition highlights the importance of advanced characterization tools and scientific interpretation in materials discovery.

- CNTs reshaped nanoscience by proving that structure and dimensionality can be as important as composition.

- Today, CNTs are actively influencing electronics, composites, sensing, energy, and biomedical technologies.

- Most importantly, CNTs serve as a gateway material, helping students understand how modern nanotechnology bridges fundamental science and real-world applications.

With this foundation, readers are now prepared to move beyond what carbon nanotubes are and how they were discovered, toward a deeper structural understanding. This naturally leads to Part 2 of the series, where we explore why graphene is the fundamental building block of carbon nanotubes and how atomic bonding gives rise to their remarkable tubular form.

References:

- Iijima, “Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon,” Nature, vol. 354, pp. 56–58, 1991. Nature

- W. Kroto, J. R. Heath, S. C. O’Brien, R. F. Curl, and R. E. Smalley, “C60: Buckminsterfullerene,” Nature, vol. 318, pp. 162–163, 1985. Nature

- V. Radushkevich and V. M. Lukyanovich, “O strukture ugleroda, obrazujuŝegosja pri termičeskom razloženii okisi ugleroda na zheleznom kontakte,” Zhurn. Fiz. Khim. (Russ.), vol. 26, pp. 88–95, 1952. SCIRP+1

- Monthioux and V. L. Kuznetsov, “Who should be given the credit for the discovery of carbon nanotubes?,” Carbon, vol. 44, no. 9, pp. 1621–1623, 2006. ResearchGate+1

- F. L. De Volder, S. H. Tawfick, R. H. Baughman, and A. J. Hart, “Carbon nanotubes: present and future commercial applications,” Science, vol. 339, no. 6119, pp. 535–539, 2013. PubMed+1

- S. Dresselhaus, G. Dresselhaus, and P. Avouris (eds.), Carbon Nanotubes: Synthesis, Structure, Properties and Applications, Springer-Verlag, 2001 (and later reprints/editions). Springer Nature Link+1

- Avouris, J. Appenzeller, R. Martel, and S. J. Wind, “Carbon nanotube electronics,” Proceedings of the IEEE, invited paper (see Avouris et al. for CNT electronics overview), 2003. forth.gr

- Grobert, “Carbon nanotubes — becoming clean,” Materials Today, vol. 10, no. 1–2, pp. 28–35, 2007. ScienceDirect

- (Optional — useful review & history) M. Paramsothy, “Seventy years since 1952 — reexamining early images and credit for carbon nanotube discovery,” Nanomaterials (special issue / review), 2023. PMC+1

Dr. Rolly Verma

Explore More from Advance Materials Lab

Continue expanding your understanding of material behavior through our specialized resources on ferroelectrics and phase transitions. Each guide is designed for research scholars and advanced learners seeking clarity, precision, and depth in the field of materials science and nanotechnology.

🔗 Recommended Reads and Resources:

-

Ferroelectrics Tutorials and Research Guides — Comprehensive tutorials covering polarization, hysteresis, and ferroelectric device characterization.

-

Workshops on Ferroelectrics (2025–2027) — Upcoming training sessions and research-oriented workshops for hands-on learning.

-

Glossary — Ferroelectrics and Phase Transitions — Concise explanations of key terminologies to support your study and research work.

- Material Science & Ceramics — A comprehensive guide to nanoceramics, electroceramics and thermodynamics.

If you notice any inaccuracies or have constructive suggestions to improve the content, I warmly welcome your feedback. It helps maintain the quality and clarity of this educational resource. You can reach me at: advancematerialslab27@gmail.com