Magnetic Phenomena in Nanoceramics: Magnetoresistance, Superparamagnetism & High-Tc Superconductivity

Nanoceramics are capturing the spotlight in modern nanotechnology because they reveal behaviours that traditional bulk ceramics could never show. When ordinary ceramic materials are shrunk down to the nanometre scale, their grain size becomes so tiny that the surface of the material—and the atomic environment at grain boundaries—begins to dominate the physics. At this scale, electrons move differently, magnetic spins interact in new ways, and the material responds to external fields with a level of sensitivity that is simply not possible in bulk form. This is why nanoceramics often exhibit striking magnetic features, including giant magnetoresistance, superparamagnetism, and even high-temperature superconductivity — properties that make them attractive for next-generation memory devices, medical imaging, energy systems, and advanced electronics.

Understanding these properties is highly beneficial for nanotechnology and materials science students, because they provide a direct link between condensed matter physics and real-world applications. In this tutorial, we will study each phenomenon in detail, examine its origin and characteristics, and explore how nanoceramics enhance these magnetic effects and make them technologically useful.

Table of Contents

Magnetoresistance

Magnetoresistance is a physical phenomenon where the electrical resistance of a material changes when an external magnetic field is applied. This effect is particularly significant in certain materials, especially magnetic nanomaterials and nanoceramics, and is widely used in modern electronic and sensing devices.

Key Concepts:

Magnetoresistance is the change in a material’s resistance in response to a magnetic field. The resistance may increase or decrease depending on the material and the orientation of the magnetic field relative to the current.

In nanoceramics, this effect becomes significantly amplified due to size-controlled electron transport. At the nanoscale, electrons experience frequent scattering at grain boundaries, and many of these scattering events depend on the alignment of electron spin. When a magnetic field is applied, the spins become more ordered and scattering decreases, which reduces resistance. When the magnetic field is removed, spin disorder increases and resistance returns to its original value. This strong correlation between spin alignment and electrical resistance forms the basis of the magnetoresistance effect.

Types of Magnetoresistances:

1. Ordinary Magnetoresistance (OMR):

Ordinary magnetoresistance is a fundamental effect exhibited by most conductive materials when subjected to an external magnetic field. It arises primarily due to the Lorentz force, which acts on the moving charge carriers (electrons) within the conductor. This force deflects the electron trajectories, thereby altering the path length and increasing the effective resistance of the material. Although the magnitude of OMR is generally small, it serves as the classical basis for understanding more complex magnetoresistive phenomena observed in advanced materials.

2. Anisotropic Magnetoresistance (AMR):

Anisotropic magnetoresistance is a characteristic feature of ferromagnetic metals such as iron, nickel, and cobalt. In this effect, the electrical resistance of the material varies systematically with the angle between the direction of electric current and the magnetization vector. When the current and magnetization are parallel, the resistance differs from the condition when they are perpendicular. This directional dependence arises due to spin–orbit coupling, which affects the scattering of conduction electrons. AMR is widely utilized in magnetic field sensors and in the read heads of early magnetic storage devices.

3. Giant Magnetoresistance (GMR):

Giant magnetoresistance represents a major advancement in spin-dependent transport phenomena. It occurs in multilayered magnetic structures consisting of alternating ferromagnetic and non-magnetic conductive layers. The key mechanism involves spin-dependent electron scattering—when the magnetizations of adjacent layers are aligned parallel, electron scattering is minimized, resulting in lower resistance. Conversely, when they are antiparallel, scattering increases, leading to higher resistance. The relative change in resistance can be extremely large, hence termed “giant.” GMR has revolutionized data storage technology and forms the foundation of modern hard disk read heads and magnetic sensors.

4. Colossal Magnetoresistance (CMR):

Colossal magnetoresistance is an extraordinary effect observed in certain manganite perovskite ceramics, such as La₁₋ₓCaₓMnO₃. In these materials, the application of a magnetic field can cause an enormous reduction in electrical resistance, often by several orders of magnitude. The underlying mechanism involves the complex interplay between charge, spin, and lattice degrees of freedom, particularly the double exchange interaction between Mn³⁺ and Mn⁴⁺ ions. CMR materials have attracted immense scientific interest due to their potential applications in spintronic devices, magnetic sensors, and advanced memory technologies.

5. Tunnel Magnetoresistance (TMR):

Tunnel magnetoresistance occurs in magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs), which consist of two ferromagnetic layers separated by a thin insulating barrier. In such structures, electrons can quantum mechanically tunnel through the barrier, and the tunneling probability depends strongly on the relative orientation of the magnetizations in the two ferromagnetic layers. When the magnetizations are parallel, tunneling is more probable, leading to low resistance; when antiparallel, tunneling is suppressed, and resistance increases. TMR is a key mechanism employed in magnetoresistive random-access memory (MRAM) and other spintronic architectures, offering non-volatility, high speed, and low power consumption.

Why Nanoceramics for MR?

Magnetoresistance — the change of electrical resistance under an applied magnetic field — is enhanced in nanoceramic materials due to the proliferation of grain-boundaries, interfaces and tunnelling pathways. In many perovskite manganites (for example La₁₋ₓSrₓMnO₃ and related systems), the grain boundary regions act as spin‐disordered or spin‐mismatched zones, leading to spin‐polarized charge tunnelling across adjacent ferromagnetic grains. This mechanism is a major contributor to low-field magnetoresistance (LFMR) in polycrystalline/ nanostructured ceramics.

Because nanoceramics increase the boundary‐to‐volume ratio, they allow more of these “weak-link” regions, making the MR effect more visible under lower magnetic fields, sometimes even at or near room temperature. This makes them appealing for sensors, magnetic switching elements, and advanced functional devices.

Practical take-aways for Nanoceramic Design

For materials scientists and nanotechnology scholars designing magnetoresistive nanoceramics, here are some practical take-aways:

- Grain/particle size matters: Smaller crystallite sizes increase boundary density, which can boost LFMR — but too small might degrade ferromagnetism or carrier mobility.

- Optimised inter‐grain boundaries: Thin, well-defined grain boundaries (rather than thick amorphous or highly disordered ones) favour spin-polarised tunnelling rather than simple scattering.

- Secondary insulating phase: Introducing a controlled insulating phase at boundaries (e.g., Mn₃O₄ in manganite composites) can enhance the effect by creating sharper potential barriers for tunnelling.

- High & saturation magnetisation: To get usable MR at or near room temperature, the ferromagnetic ordering must persist at high temperature; hence, composition and doping must be selected for a high.

Different types of magnetoresistances have been experimentally observed in nanoceramic systems. For example, giant magnetoresistance (GMR) occurs in multilayer structures where ferromagnetic and non-magnetic layers are alternately stacked. Colossal magnetoresistance (CMR) appears in manganite-based nanoceramics such as La₁₋ₓCaₓMnO₃, where electron–lattice interactions combine with spin ordering to produce dramatic resistance changes. Tunnel magnetoresistance (TMR) is seen when electrons tunnel through a thin insulating barrier between two magnetic layers and the tunneling probability depends on relative spin orientation.

The high sensitivity of magnetoresistance to the external magnetic field makes MR-based nanoceramics ideal for miniaturized magnetic field sensors, high-density memory devices, and modern spintronic components. As synthesis techniques improve, especially with thin-film deposition and spark plasma sintering, nanoceramics continue to produce stronger magnetoresistive performance suitable for industrial-scale applications.

Superparamagnetism

Superparamagnetism is the enhanced version of paramagnetism which specifically occurs in nanostructured magnetic materials. In paramagnetism, the magnetic behaviour of the materials becomes weakly magnetized in the presence of an external magnetic field, but do not retain magnetism once the field is removed. This temporary magnetic effect is due to the presence of unpaired electrons in the atoms or ions of the material, which align their magnetic moments with the applied magnetic field. Superparamagnetism is the “collective version” of paramagnetism.

Superparamagnetism in Nanoceramics

Superparamagnetism is a special magnetic phenomenon observed in nanoparticles of ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic materials when the particle size becomes extremely small, typically below 20 to 30 nanometers. At this size scale, each nanoparticle behaves as a single magnetic domain, and its entire magnetic moment can flip direction freely under thermal energy. In the absence of an external magnetic field, the magnetization of these nanoparticles averages to zero over time, meaning they do not retain magnetic memory. However, when a magnetic field is applied, they exhibit strong magnetization similar to paramagnetic materials but with much higher susceptibility. Each nanoparticle behaves like single magnetic domains and can spontaneously flip their magnetic direction under the influence of thermal energy. This means that, although the material is magnetic, it does not retain permanent magnetization when an external magnetic field is removed—much like a paramagnet, but with much stronger magnetic susceptibility.

Why It Happens:

In bulk ferromagnetic materials, domains align in a certain direction, and magnetic memory (remanence) is retained even after the field is removed.

But in nanoparticles below a critical size (typically < 20–30 nm), the entire particle acts as one magnetic domain, and thermal fluctuations become strong enough to flip the direction of magnetization randomly.

As a result:

- No hysteresis loop is observed.

- Zero coercivity and zero remanence are seen at room temperature.

Key Characteristics of Superparamagnetic Materials:

- High magnetic susceptibility (respond strongly to external magnetic fields)

- No residual magnetism after field removal

- No energy loss due to hysteresis

- Fast response to magnetic field changes

- Behaviour depends strongly on particle size and temperature

Examples of Superparamagnetic Nanomaterials:

A clear demonstration of this effect is seen in CoFe₂O₄ nanoparticles with grain sizes of about 6–9 nm, which exhibit a saturation magnetization of ~70 A·m²/kg (≈ 70 emu/g) and extremely low coercivity (~0.9 mT) at 300 K, confirming a true superparamagnetic state (Zorai et al., 2023).

Another notable example is a MnFe₂O₄@SiO₂ core–shell nanoceramic with an overall size of around 26 nm, which also shows room-temperature superparamagnetism with while simultaneously supporting NIR optical emission — proving the feasibility of multifunctional magnetic–optical nanoceramics (Casteleiro et al., 2023)

This magnetic behavior is highly important in nanotechnology because it eliminates magnetic hysteresis and energy loss. Nanoceramic ferrite materials such as Fe₃O₄ and CoFe₂O₄ are widely studied for their superparamagnetic behavior. The blocking temperature, which represents the temperature below which magnetic moment flipping stops, plays a key role in determining whether a superparamagnetic material behaves like a regular ferromagnet or maintains its superparamagnetic state.

The ability to respond strongly to magnetic fields without retaining permanent magnetization makes superparamagnetic nanoceramics excellent candidates for biomedical and sensing applications. They are widely used in MRI contrast enhancement, targeted drug delivery, magnetic hyperthermia for cancer treatment, magnetic separation, miniaturized biosensors, and nanomagnetic memory research. Their usefulness increases further when surface coatings, biocompatibility treatments, or functionalization are applied.

High-Tc Superconductors

High Tc materials, or high-temperature superconductors, are materials that can conduct electricity without any resistance at relatively higher temperatures than traditional superconductors. Here, Tc stands for “critical temperature”, which is the temperature below which a material becomes superconducting.

High-Tc materials, also called high-temperature superconductors, are a special group of materials that can conduct electricity with zero resistance, but unlike traditional superconductors, they do this at much higher temperatures. The term Tc means critical temperature, which is the point below which a material suddenly becomes superconducting. In ordinary superconductors such as elemental mercury, the transition into the superconducting state only happens extremely close to absolute zero — around 4 K (-269 °C). Cooling to such an extreme temperature requires the use of liquid helium, which is costly and difficult to handle.

High-Tc materials changed everything because they entered the superconducting state at much more practical temperatures. Many of them can become superconducting at or above 77 K (-196 °C) — the boiling point of liquid nitrogen. This matters because liquid nitrogen is cheap, easy to store, and widely available, unlike liquid helium. Because of this, high-Tc superconductors made superconductivity much more realistic for real-world applications rather than just laboratory demonstrations.

Among high-Tc materials, some names appear frequently in research and industry. One of the earliest and most important examples is YBCO (Yttrium Barium Copper Oxide), which becomes superconducting at around 92 K, comfortably above the liquid nitrogen limit. Another widely studied compound is BSCCO (Bismuth Strontium Calcium Copper Oxide), which shows a critical temperature of about 108 K. There are also mercury-based cuprates such as HgBa₂Ca₂Cu₃O₈, which can reach critical temperatures as high as 133 K under normal pressure, one of the highest values discovered so far. Even though these materials are called ceramics, they are electrically extraordinary — when the temperature falls below Tc, their resistance drops to zero and their magnetic behaviour changes dramatically.

The physics of how high-Tc superconductors work is still one of the most fascinating mysteries in modern materials science. In low-temperature superconductors, the BCS theory explains superconductivity very well: electrons pair together due to lattice vibrations, forming what we call Cooper pairs. High-Tc materials, however, are much more complex. They are mostly copper-oxide ceramics (known as cuprates) where superconductivity arises from strong electron interactions in the copper–oxygen planes. These interactions are not fully explained by traditional theories, which is why high-Tc superconductivity remains an active and exciting research field.

Magnetic response is another remarkable characteristic of high-Tc superconductors. When cooled below their critical temperature, they not only allow current to flow with zero resistance, but they also push magnetic fields out of their interior — a phenomenon known as the Meissner effect. If a magnet is placed near a superconducting material in this state, the magnetic field lines can become pinned rather than freely expelled. This process, known as flux pinning, creates very stable magnetic levitation. It is the same principle behind dramatic demonstrations where a magnet appears to float or glide friction-free over a superconducting disk.

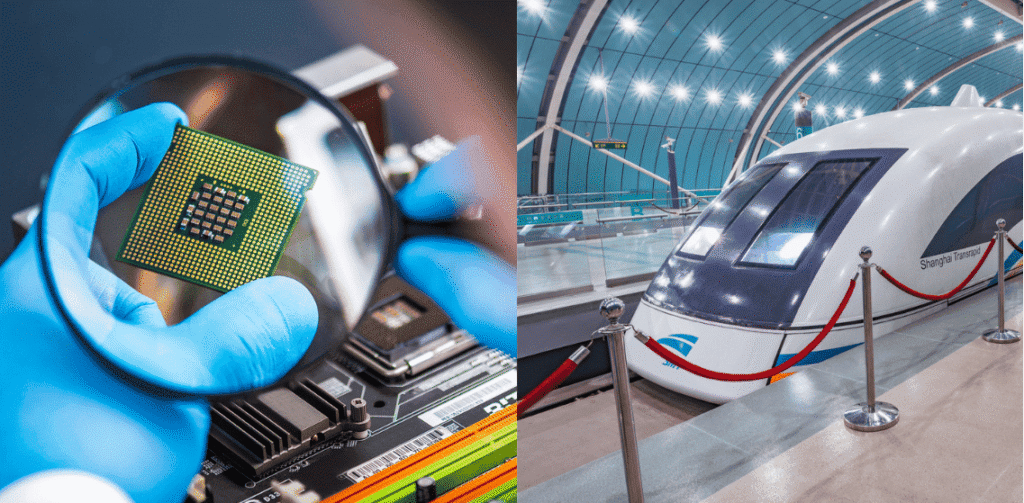

Because of their unique electronic and magnetic behaviour, high-Tc superconductors already play a crucial role in modern technology. They are used in MRI machines, scientific research magnets, and ultra-sensitive magnetic sensors called SQUIDs. Researchers are also developing high-Tc superconducting power cables that can transmit electricity with no loss, maglev trains that can levitate using flux pinning, and quantum computing components based on superconducting circuits. Improving flux-pinning performance through nanostructuring is currently one of the most important research directions because it directly enhances the magnetic stability required for these advanced applications.

In summary, high-Tc superconductors are a breakthrough in materials science because they bring superconductivity out of extremely low-temperature laboratory conditions and into a temperature range where large-scale, real-world technology becomes possible. Their exceptional electrical and magnetic properties — combined with the practicality of using liquid nitrogen for cooling — make them one of the most promising material groups for the future of energy, transportation, electronics and quantum technology.

Latest Research & Discoveries (2022–2025) — Explained in Simple Words

Scientists are making fast progress in the field of magnetic nanoceramics, and the latest studies show interesting developments:

- The remarkable features of especially large colossal magnetoresistance (CMR) and high temperature coefficient of resistance (TCR) — LCMO thin films are now being used in a wide range of advanced technologies such as biometrics, night-vision cameras, thermal sensors, magnetic refrigeration systems, and artificial planar junctions.

- Many research groups are actively studying the resistive switching behavior of LCMO for non-volatile memory devices. If this research becomes commercially successful, it could enable faster, more durable, and energy-efficient memory storage compared to the present technologies.

- The latest research showed that the magnetic nanoparticles made of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles (CFNPs) and iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) can successfully attach to the human haemoglobin (a protein in blood), and carrying medicine to specific places inside the body which may be very helpful in future cancer-treatment methods.

- Cuprate superconductors will power future technologies by enabling a new generation of zero-loss energy infrastructure and compact, high-field medical scanners that require less expensive cooling. Their unique properties also offer promising pathways for developing next-generation quantum computers and efficient high-speed transportation systems like maglev.

- Superconductors (like YBCO and BSCCO) are special materials that can carry electricity without wasting energy. Scientists have recently found that under high pressure, these materials may work at higher temperatures than ever before. If this becomes practical, cities could get electricity with almost zero energy loss, trains could levitate and travel extremely fast, computers could become hundreds of times more powerful. This is the type of technology that can change transportation, medicine, and the whole energy system of the world.

Final Remarks

Magnetic phenomena in nanoceramics reveal how drastically material behavior can change when particle size enters the nanometer scale. Whether it is giant changes in electrical resistance, loss of magnetic hysteresis, or zero electrical resistance, nanoscale structuring plays a central role. Understanding these interactions enables scientists and engineers to design smarter sensors, faster memory devices, advanced medical diagnostics, energy-efficient superconducting systems and next-generation transportation technologies.

In short — nanoceramics are not just academically interesting; they are transforming modern technology.

References

- Ziese, M. & Thornton, M. (Eds.). Spin Electronics. Lecture Notes in Physics, Vol. 569, Springer, 2001.

Sun, S., Murray, C. B., Weller, D., Folks, L., & Moser, A. “Monodisperse FePt nanoparticles and ferromagnetic FePt nanocrystal superlattices.” Science, 287(5460), 1989–1992 (2000).

DOI: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1989Pankhurst, Q. A., Connolly, J., Jones, S. K., & Dobson, J. “Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine.” Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 36(13), R167–R181 (2003).

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S., & Zaanen, J. “High-temperature superconductivity in the cuprates.” Nature, 518, 179–186 (2015).

Bednorz, J. G. & Müller, K. A. “Possible high Tc superconductivity in the Ba–La–Cu–O system.” Zeitschrift für Physik B Condensed Matter, 64, 189–193 (1986).

Dagotto, E. “Complexity in strongly correlated electronic systems.” Science, 309(5732), 257–262 (2005).

DOI: 10.1126/science.1107559

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Why does magnetoresistance increase at the nanoscale?

Because electron scattering becomes more sensitive to spin alignment when grain boundaries and interfaces dominate electron transport.

Q2: Why don’t superparamagnetic nanoparticles behave like permanent magnets?

Thermal energy at room temperature randomizes the direction of magnetic moments, causing zero magnetization in the absence of an external field.

Q3: Can high-temperature superconductors work at room temperature?

Not yet — but several cuprate ceramic materials show superconductivity at temperatures far higher than conventional metallic superconductors, and research is progressing rapidly.

Q4: Are these nanoceramic materials commercially used today?

Yes. Magnetoresistive sensors are widely used in electronics and automobiles; superparamagnetic nanoparticles are used clinically; and high-Tc superconductors are used in MRI machines and Maglev systems.

Dr. Rolly Verma

Continue your learning journey with these student-friendly guides and tutorial notes on AdvanceMaterialsLab.com.

For readers interested in high-temperature superconductors and their role in next-generation energy and transportation systems, you can explore our detailed guide on yttrium barium copper oxide (YBCO): 🔗 YBCO Superconductor — Properties & Applications

If you want to understand how nanoceramics enhance mechanical, thermal, and electronic performance in modern devices, you may find this article helpful:🔗 Nanoceramics — Properties & Advancements

For beginners or students studying material science, this simple explanation of thermodynamic properties helps in understanding how materials behave under different physical conditions:

🔗 Thermodynamic — Extensive & Intensive Concept

Readers exploring smart materials and memory applications may also benefit from our step-by-step tutorial on ferroelectrics, including working principles and research trends:

🔗 Ferroelectrics — Tutorials & Research Guides

If you notice any inaccuracies or have constructive suggestions to improve the content, I warmly welcome your feedback. It helps maintain the quality and clarity of this educational resource. You can reach me at: advancematerialslab27@gmail.com