Understanding the Laws of Thermodynamics: A Foundational Guide for Materials Science Students

Thermodynamics is the fundamental pillars of materials science and engineering. It provides the scientific framework for understanding how energy and matter interact, how materials respond to heat, pressure, and work, and why certain physical and chemical transformations occur while others do not. From the melting of metals and sintering of ceramics to phase transformations in alloys and polarization switching in ferroelectrics — every material phenomenon is governed by the laws of thermodynamics. These laws describe the flow of energy, the direction of natural processes, and the conditions for equilibrium.

For students of materials science, thermodynamics is not just an abstract theory — it is the language of energy that connects atomic behaviour with engineering applications. Understanding these laws helps predict material stability, design new compounds, control heat treatments, and even optimize processes like crystal growth, thin-film deposition, and battery operation.

In this tutorial, we simplify the Laws of Thermodynamics — the Zeroth, First, Second, and Third Laws — with clear explanations, real-world material examples, and academic clarity. We will learn:

- How temperature is defined and measured (Zeroth Law)

- How energy is conserved in all physical and chemical changes (First Law)

- How entropy dictates the direction of spontaneous processes (Second Law)

- How absolute zero defines the limit of order in perfect crystals (Third Law)

Each law of thermodynamics complements the others, together forming a comprehensive framework for understanding thermodynamic stability, equilibrium, and energy transformations in materials.

By the end of this blog, you will develop a confident understanding of how these fundamental laws govern the behaviour, structure, and functionality of materials — spanning from classical metals and alloys to modern quantum and nanoscale systems.

Table of Contents

Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics: The Foundation of Temperature

The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics, though seemingly simple, represents the most fundamental principles in physics and materials science. It defines the very foundation of temperature measurement — a critical parameter without which thermodynamic analysis and material characterization would be impossible.

Historical Background:

Before the 20th century, scientists already knew the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics, but they lacked a formal law that defined thermal equilibrium and the concept of temperature itself.

In the early 1930s, British physicist Ralph H. Fowler and his contemporaries observed that while the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics depended on the concept of temperature equilibrium, neither explicitly defined it. To address this foundational gap, Fowler and his colleagues formally introduced the Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics in 1931. The term “Zeroth” was selected both humorously and logically — signifying that, although formulated later, it underpins the very basis upon which the other laws stand.

Statement and Interpretation

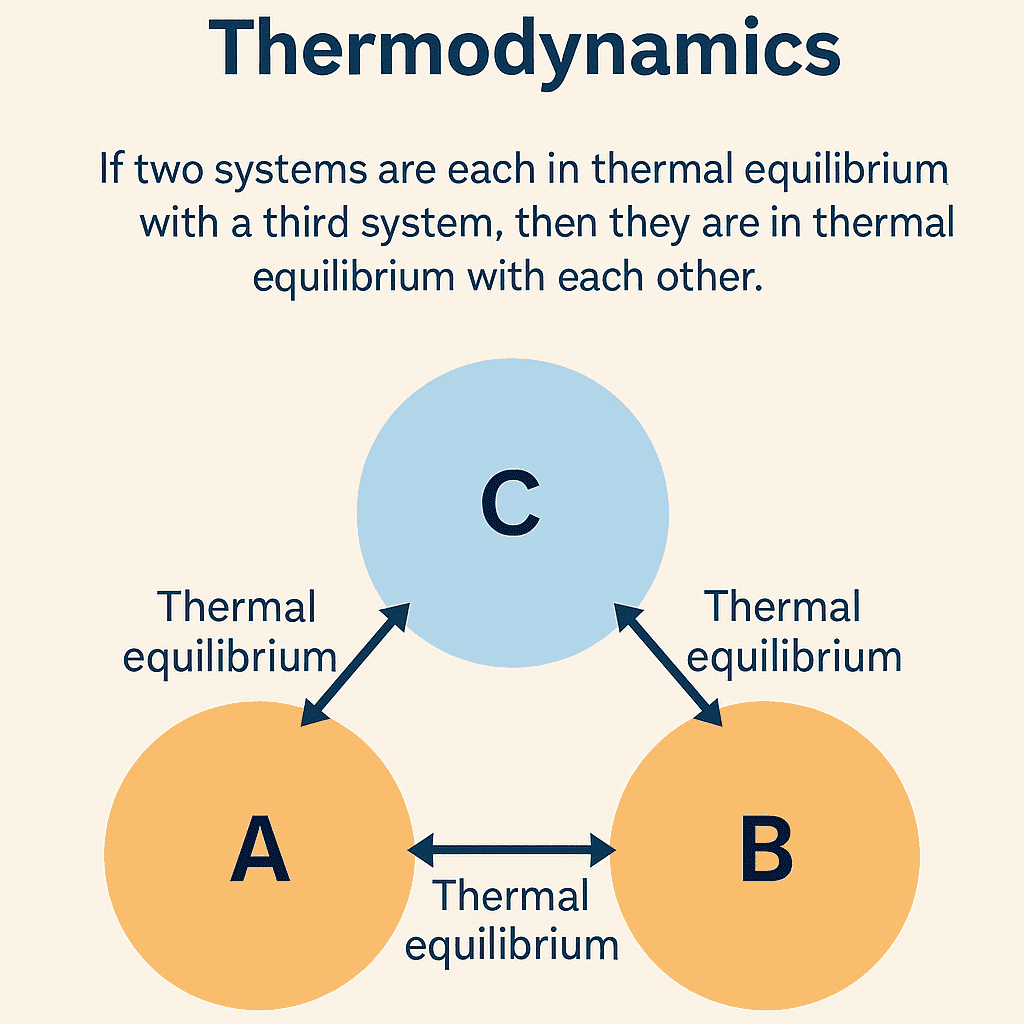

The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics states that:

If two systems (A and B) are each in thermal equilibrium with a third system (C), then A and B are in thermal equilibrium with each other.

This law might appear straightforward, but its implications are profound. It tells us that temperature is a transitive property — a measurable and comparable quantity between different systems. If system A has the same temperature as system C, and system B also matches system C, then all three share the same temperature. When there is no net exchange of heat between two bodies in contact, they are said to be in thermal equilibrium. This equilibrium can exist only when both bodies have the same temperature. This simple statement allows scientists to define temperature scales and construct thermometers.

For example, when a thermocouple touches a hot metal surface during an experiment, heat flows until both reach the same temperature. Once equilibrium is achieved, the thermocouple reading accurately represents the material’s temperature. This principle forms the basis of every temperature measurement instrument — from mercury thermometers to infrared pyrometers and digital sensors.

Why the Zeroth Law Matters in Materials Science

In materials science, precise temperature measurement is essential in almost every process:

- During annealing or sintering, the temperature must remain uniform across the material for consistent grain growth.

- In phase transformation studies, such as melting, crystallization, or diffusion, temperature equilibrium ensures reliable and reproducible data.

- When studying ferroelectric or piezoelectric materials, maintaining a constant temperature helps researchers accurately determine polarization and hysteresis behavior.

Without the Zeroth Law, there would be no consistent way to define temperature — and therefore, no standard way to study material properties.

✅ Key Concept Summary

- Discovered and formalized by Ralph H. Fowler (1931).

- Establishes the concept of temperature and thermal equilibrium.

- States that if A = C and B = C in temperature, then A = B.

- Forms the foundation for all thermometry and temperature-dependent experiments in materials science.

First Law of Thermodynamics: The Principle of Energy Conservation in Materials

The First Law of Thermodynamics stands as the cornerstone of all physical sciences, asserting the conservation of energy in nature. It states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed — it can only transform from one form to another. In the realm of materials science, this principle governs every process — from melting and solidification to phase transitions and stress-induced transformations — ensuring that the total energy in a system and its surroundings remains constant.

Historical Background:

The origins of the First Law trace back to the 19th century, a period when scientists began uncovering the relationship between mechanical work and heat. At that time, many physicists believed in the caloric theory, which proposed that heat was a subtle, fluid-like substance that flowed from hot to cold bodies. However, a series of meticulous experiments soon disproved this misconception and established heat as a form of energy.

The formulation of the First Law was shaped by the contributions of three pioneering scientists:

- James Prescott Joule (1843–1849) — Through his paddle-wheel experiment, Joule demonstrated that mechanical work can be precisely converted into heat energy. His experiments quantified this relationship, introducing the concept of the mechanical equivalent of heat and laying the foundation for modern energy measurement.

- Rudolf Clausius (1850) — Clausius gave the law its mathematical formulation, expressing it in terms of changes in internal energy within a thermodynamic system. His work bridged the gap between mechanics and thermodynamics.

- Hermann von Helmholtz (1847) — Helmholtz extended the concept to all fields of science by articulating the Principle of Conservation of Energy, asserting that energy remains constant across all natural phenomena, whether mechanical, chemical, or biological.

Mathematical Formulation

The First Law is expressed as:

ΔU = Q − W

-

In words: the change in a system’s internal energy equals the heat supplied minus the work performed.

If a system absorbs heat, its internal energy increases. If it does work (for example, during expansion),

its internal energy decreases.

Physical Interpretation of the First Law

The First Law of Thermodynamics reveals that heat and work are simply two distinct modes of energy transfer between a system and its surroundings. Energy can enter or leave a material system, but the total energy of the universe remains constant — it only changes its form, never being lost or created from nothing.

In the context of materials science, this law provides a powerful framework to understand how materials respond to thermal and mechanical interactions:

- Heat input increases the vibrational energy of atoms, leading to a rise in temperature or thermal expansion.

- Mechanical work done on a material can result in elastic or plastic deformation, dislocation motion, or even phase transformations.

- The internal energy (U) represents the sum of all microscopic energy contributions within the material — including lattice vibrations, bonding energies, electronic excitations, and defect-related energies.

Hence, the First Law serves as a bridge between macroscopic observables (like heat, work, and temperature) and microscopic phenomena occurring at the atomic and electronic scales. It explains how every thermal or mechanical process is ultimately a manifestation of energy transformation within matter.

Conceptual Example

Imagine a metal rod being mechanically compressed:

- When external work is applied to compress the rod, its internal energy increases.

- This increase appears as a rise in temperature, since deformation generates heat within the material.

- When the rod is released and allowed to expand, it performs work on its surroundings, leading to a slight cooling effect.

This simple scenario beautifully demonstrates the First Law of Thermodynamics — energy is continuously exchanged between heat and work, but never lost or created.

Significance in Thermodynamic Systems

In materials science, the First Law of Thermodynamics plays a crucial role in understanding and controlling energy transformations. It allows us to:

- Calculate energy balances during processes such as sintering, oxidation, and chemical reactions.

- Determine enthalpy changes (ΔH) through precise calorimetric measurements.

- Evaluate specific heat capacities and assess the thermal stability of materials.

- Predict energy requirements for operations like melting, solidification, and thin-film deposition.

Every modern materials process — from semiconductor fabrication to polymer extrusion — fundamentally follows this law of energy conservation.

✅ Key Concept Summary

- Discovered through experiments by James Prescott Joule (1840s).

- Formulated mathematically by Clausius and Helmholtz.

- Explains that heat and work are interchangeable energy forms.

- Forms the foundation for energy analysis in all material processes.

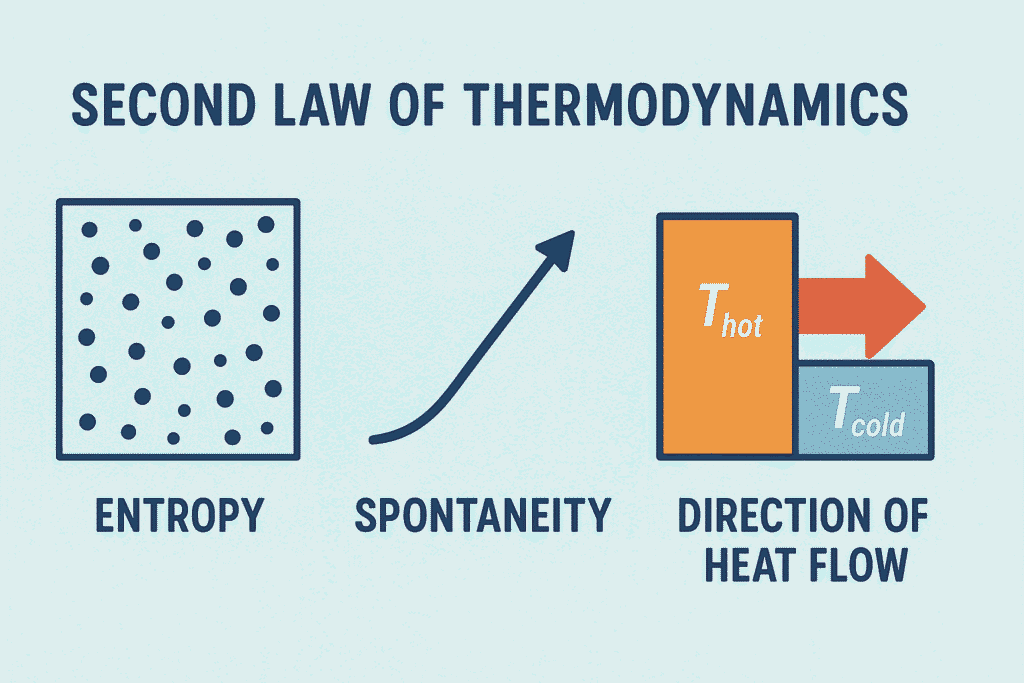

Second Law of Thermodynamics: Entropy, Spontaneity, and the Direction of Change

The Second Law of Thermodynamics stands as a cornerstone of physical science, defining the directionality of natural processes and the concept of irreversibility. The Second Law explains why every process in nature has a preferred direction and introduces the concept of entropy (S) — a fundamental measure of disorder and energy dispersal. In materials science, this law governs diffusion, phase transformations, heat transfer, and reaction spontaneity, making it indispensable for understanding and predicting how materials change and evolve over time.

Historical Background:

The Second Law of Thermodynamics took shape during the 19th century through the study of heat engines and energy conversion. Several pioneering scientists contributed to its development, each adding a crucial piece to our understanding of energy flow and irreversibility.

- Sadi Carnot (1824):

Often called the father of thermodynamics, Carnot studied how steam engines convert heat into work. He discovered that no engine can transform all the supplied heat into useful work — some energy is always lost as waste heat. Carnot introduced the concept of a reversible cycle, which set the theoretical limit for engine efficiency and laid the foundation for the Second Law. - Rudolf Clausius (1850):

Clausius advanced thermodynamic theory by introducing the term entropy (S) and defining it mathematically. He explained that natural processes always proceed in a direction that increases the total entropy of the universe. His work clarified why systems naturally evolve from more ordered to less ordered states, establishing the idea of irreversibility in physical processes. - Lord Kelvin (William Thomson):

Kelvin expressed the same principle in terms of the availability of energy. He stated that it is impossible to create a cyclic device that converts all absorbed heat from a single reservoir entirely into work. His formulation highlighted the limitations on energy conversion, emphasizing that some energy always becomes unavailable for useful work.

Together, these discoveries established the core idea of the Second Law — that every real transformation is accompanied by an increase in entropy, which determines the natural direction of all physical and material processes.

Different Statements of the Second Law of Thermodynamics

The Second Law of Thermodynamics can be expressed in several equivalent ways, each highlighting a different aspect of how energy behaves in natural processes:

- Clausius Statement:

Heat never flows on its own from a colder body to a hotter one.

This means that spontaneous heat transfer always occurs from high temperature to low temperature, defining the natural direction of heat flow. - Kelvin–Planck Statement:

No engine can convert all the heat it absorbs from a single heat source entirely into work.

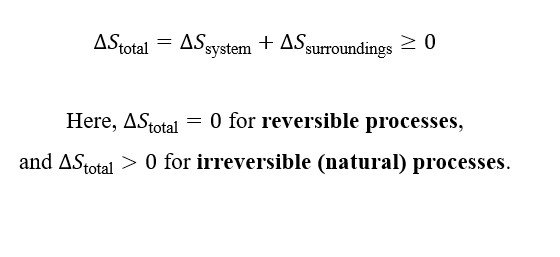

This emphasizes that some energy is always lost as waste heat, making 100% efficient heat engines impossible. - Entropy Statement:

In every real process, the total entropy of an isolated system always increases.

This version connects the Second Law directly to entropy (S), showing that natural processes move toward greater disorder or energy dispersal until equilibrium is reached.

Physical Meaning of Entropy

Entropy is a thermodynamic property that measures the degree of randomness, disorder, or energy dispersal in a system. It indicates how energy is distributed among the microscopic particles — atoms, ions, or molecules — that make up the material.

In simple terms, entropy measures the “spread” or “dispersal” of energy;

- High entropy → More randomness and more possible arrangements (e.g., gas molecules moving freely in a container).

- Low entropy → More ordered and fewer possible arrangements (e.g., atoms arranged in a solid crystal lattice).

What is High Entropy ?

High entropy describes a state in which a system exhibits a high degree of randomness and disorder at the microscopic level. In such a condition, the particles—atoms, ions, or molecules—move freely, occupy many possible positions, and exchange energy in countless ways. This freedom of motion creates a large number of possible microscopic arrangements, or microstates, that all correspond to the same overall macroscopic state.

A high-entropy system is therefore less ordered and more chaotic, with no fixed pattern or structure. The energy and matter within it are spread out and distributed as evenly as possible, rather than being concentrated in specific regions or particles.

From a physical perspective, high entropy represents a state of maximum disorder, extensive randomness, and widespread energy dispersal. Such states are statistically more probable because there are many ways for the particles to be arranged while still maintaining the same total energy.

In summary, high entropy corresponds to high randomness, high disorder, and high probability, reflecting the natural tendency of systems to evolve toward more dispersed and energetically uniform configurations.

Common Examples:

- Gas molecules in a container:

Gases exhibit very high entropy because their molecules move freely in all directions, occupying a large volume with minimal restrictions. - Liquid water:

Liquids have moderately high entropy. Although molecular motion is more restricted than in gases, molecules can still move and rearrange freely, creating many possible microstates. - Mixed systems:

When two substances mix, such as gases or alloys, entropy increases because the number of possible arrangements of their particles becomes much larger. - Dissolution:

When salt dissolves in water, ions disperse uniformly throughout the solution. This uniform distribution of particles increases entropy significantly.

What is Low Entropy ?

Low entropy describes a state in which a system exhibits a high degree of order and low randomness in the arrangement and motion of its particles. In such a condition, atoms or molecules occupy specific, well-defined positions and have limited freedom to move or exchange energy. As a result, the system has few possible microscopic arrangements (microstates) and a relatively stable, organized structure.

A low-entropy system is highly ordered, with energy and matter concentrated rather than dispersed. The particles tend to follow regular patterns—such as those found in a crystal lattice or a solid—where every atom maintains a predictable position relative to its neighbours. Because the system has fewer ways to rearrange itself without changing its overall energy, its entropy remains low.

From a physical standpoint, low entropy represents a state of minimal disorder and restricted randomness. The energy of the system is localized within specific regions or bonds, rather than being spread evenly throughout. Such states are statistically less probable because there are fewer possible configurations that maintain this high degree of order.

In summary, low entropy corresponds to low randomness, high order, and low probability. Systems in low-entropy states—such as solids or materials at low temperature—are structurally organized and energetically concentrated. When energy is added or when constraints are removed, these systems tend to move toward higher-entropy conditions, where disorder and randomness increase naturally.

Common Examples:

- Crystalline solids:

A perfect crystal at absolute zero has the lowest possible entropy because its atoms are fixed in a rigid, highly ordered arrangement with minimal motion. - Cold, condensed substances:

Substances at low temperatures generally have lower entropy because their particles have less kinetic energy and reduced random motion. - Separated mixtures:

When two substances are completely separated, entropy is lower compared to when they are mixed. Separation limits the number of possible microstates. - Condensation and freezing:

When the vapour condensed into the liquid or the liquid freezes into the solid, entropy decreases because molecular motion becomes restricted and the system becomes more ordered.

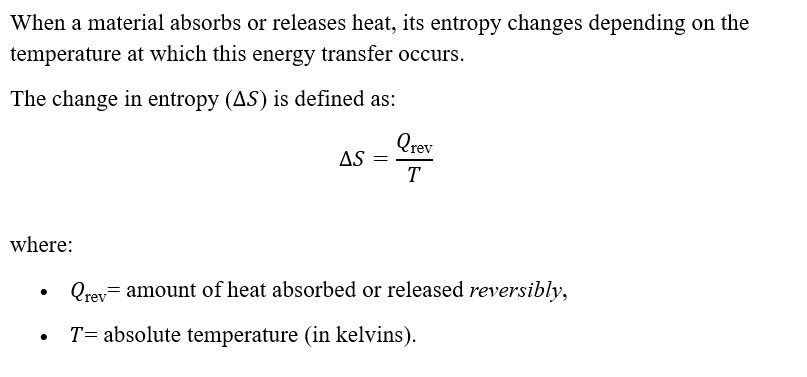

Entropy and Heat Transfer

This means that adding heat to a system increases its entropy, while removing heat decreases it.

Interpretation:

- When heat is added to a system (Qrev > 0), the particles gain energy, move more freely, and the system’s entropy increases.

- When heat is removed (Qrev < 0), particle motion becomes more restricted, and the system’s entropy decreases.

- Phase transformations: Systems naturally shift toward states with higher overall entropy and lower free energy.

Applications in Materials Science:

The Second Law of Thermodynamics forms the theoretical foundation for understanding spontaneous changes in materials. It explains why certain physical and chemical processes occur naturally while others require external energy input. In materials science, this law governs a wide range of phenomena that determine how materials form, transform, and respond to their environment.

- Diffusion Processes

Atoms and ions naturally migrate from regions of high concentration to low concentration — a spontaneous process driven by an increase in entropy. As the system becomes more disordered, its entropy rises until a uniform composition (equilibrium) is reached.

In materials applications, diffusion governs processes such as alloy homogenization, impurity doping in semiconductors, and thermal treatments, where the system evolves toward maximum randomness and minimum energy.

- Phase Transformations

During a phase change such as melting, vaporization, or sublimation, entropy increases because atoms or molecules gain greater freedom of motion and occupy a larger number of possible configurations.

For example, when a solid melts into a liquid or a liquid evaporates into a gas, the increase in molecular disorder makes these transformations spontaneous at high temperatures. In materials synthesis and processing, the Second Law helps predict which phase is thermodynamically stable under given temperature and pressure conditions.

- Heat Flow and Thermal Conductivity

According to the Second Law, heat always flows spontaneously from a region of higher temperature to one of lower temperature — never in the reverse direction without external work.

In materials science, this principle explains thermal gradients, heat dissipation, and energy transport during fabrication, sintering, and device operation. Understanding entropy-driven heat flow is crucial in designing thermal barrier coatings, semiconductor devices, and energy-efficient materials.

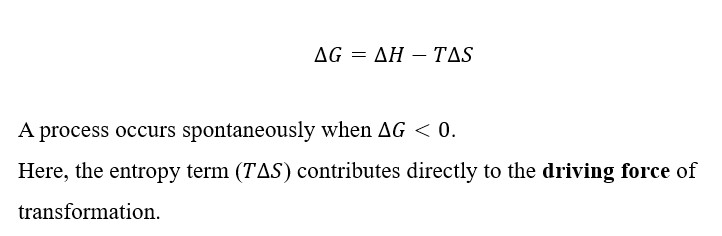

- Chemical Reactions and Thermodynamic Stability

The spontaneity of any chemical reaction or phase transformation in materials is determined by the Gibbs free energy equation:

For example, solid–solid phase transitions, oxidation of metals, and formation of compounds depend on how changes in entropy influence Gibbs free energy. The Second Law thus provides the basis for predicting the stability and direction of reactions in materials systems.

- Entropy in Crystallization and Amorphous Systems

During crystallization, a material becomes more ordered — its entropy decreases. However, the surroundings gain entropy due to the release of latent heat, ensuring that the total entropy of the universe still increases.

This illustrates the Second Law perfectly: even when a material itself becomes ordered, the overall entropy (system plus surroundings) must rise. The concept also explains why amorphous materials (which are more disordered) have higher entropy than their crystalline counterparts.

“No real process — from crystal growth to energy conversion — can occur without obeying the Second Law.”

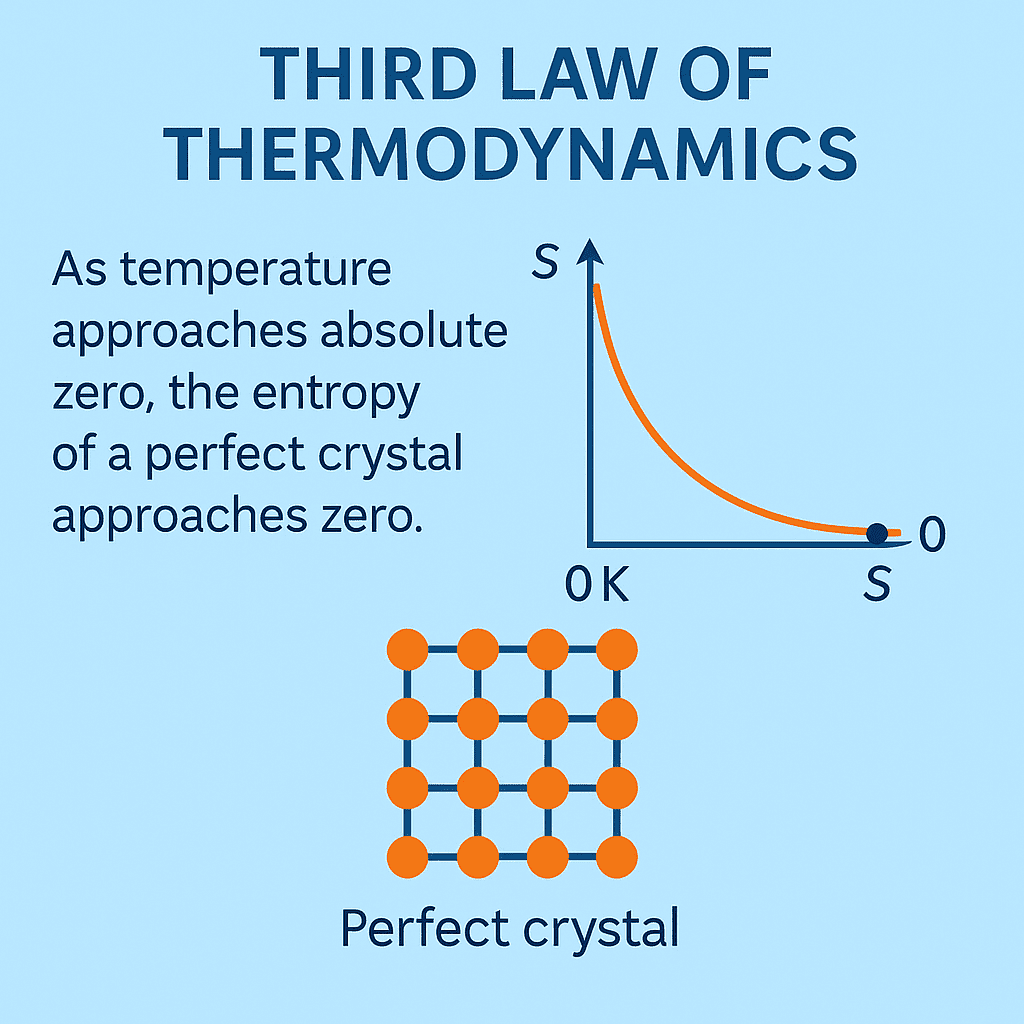

Third Law of Thermodynamics: The Absolute Zero and the Quest for Perfect Order

The Third Law of Thermodynamics takes thermodynamics to its ultimate boundary — describing how matter behaves as its temperature approaches absolute zero (0 K). It reveals how entropy, the measure of disorder in a system, approaches a minimum at these extremely low temperatures, forming the scientific basis for low-temperature physics, cryogenics, and quantum materials research.

Historical Background:

The Third Law of Thermodynamics emerged in the early 20th century, when scientists began studying how substances behave at extremely low temperatures — close to absolute zero (0 K). Their work revealed that as temperature decreases, both the motion and disorder of particles reduce dramatically, leading to important insights about entropy at the lowest possible energy states.

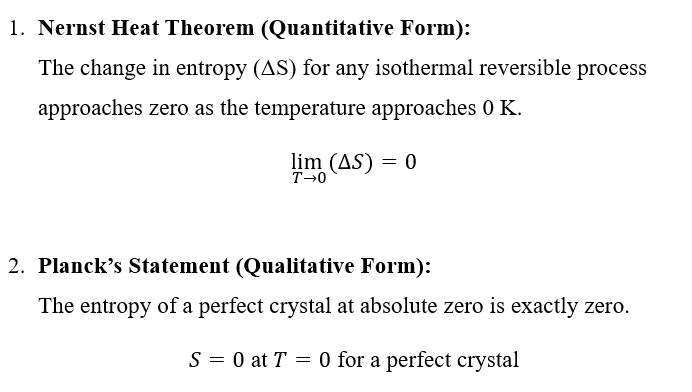

- Walther Nernst (1906):

The German physical chemist Walther Nernst first proposed what became known as the Nernst Heat Theorem, which later evolved into the Third Law of Thermodynamics.

Nernst discovered that as a system’s temperature approaches absolute zero, the entropy change for any reversible process tends to zero.

His research aimed to make thermochemical calculations more accurate and to predict chemical equilibria at very low temperatures. This was a major step in connecting entropy, temperature, and equilibrium behavior. - Max Planck (1912):

Building on Nernst’s findings, Max Planck refined and restated the principle in its modern form:

“As temperature approaches absolute zero, the entropy of a perfect crystal approaches zero.”

Planck’s statement introduced the idea of perfect order — meaning that at 0 K, a perfectly crystalline material has only one possible microscopic configuration (complete structural order, no randomness).

Together, the contributions of Nernst and Planck gave the Third Law of Thermodynamics its final form. It established an absolute reference point for entropy and completed the classical framework of thermodynamics, complementing the Zeroth, First, and Second Laws.

This law not only deepened our understanding of entropy but also provided a foundation for low-temperature physics, cryogenics, and materials research, where precise measurements near absolute zero are essential.

Theoretical Statement and Interpretation:

The Third Law of Thermodynamics can be stated in two main forms:

Applications in Materials Science

The Third Law of Thermodynamics plays a key role in understanding how materials behave at very low temperatures, especially in advanced and quantum materials research. Let’s explore its main applications in a clear and student-friendly way:

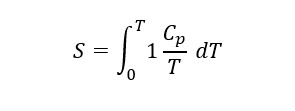

- Determination of Absolute Entropy

By integrating the specific heat (Cp) divided by temperature over the range from 0 K to room temperature, the absolute entropy of substances can be calculated.

This allows the calculation of free energy (G) and equilibrium constants, essential for predicting phase stability and chemical reactions at various temperatures.

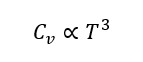

- Specific Heat Behaviour at Low Temperatures

At low temperatures, the specific heat of solids decreases sharply, following the Debye T³ law:

This law originates from quantized lattice vibrations (phonons).

In materials research, this helps analyze thermal conductivity, phonon scattering, and quantum effects in crystals and nanostructures.

- Phase Transitions and Residual Entropy

The Third Law predicts that entropy changes (ΔS) during phase transformations tend to zero as temperature approaches 0 K.

This principle explains why certain phase transitions (like order–disorder transformations in alloys) slow down or freeze at cryogenic temperatures.

- Cryogenics and Low-Temperature Material Studies

The law defines the theoretical limit for cooling techniques — absolute zero can never be reached, only approached asymptotically.

This governs cryogenic technologies used in superconductivity research, quantum computing materials, and Bose–Einstein condensates.

- Superconductivity and Quantum Effects

In superconductors, as temperature decreases, the entropy drops dramatically as electrons pair into a perfectly ordered quantum state (Cooper pairs).

The transition from a normal metal to a superconducting phase is an elegant demonstration of the Third Law in quantum materials.

Final Words

The laws of thermodynamics are the universal principles that govern every energy transformation in nature — and therefore, every process in materials science. Together, they form the logical and mathematical foundation for understanding how materials behave, transform, and reach equilibrium under different physical and chemical conditions.

The Zeroth Law defines temperature and establishes the concept of thermal equilibrium, enabling accurate temperature measurement in experiments and material processing.

The First Law ensures the conservation of energy, explaining how heat and work interact to change a system’s internal energy during melting, solidification, or mechanical deformation.

The Second Law introduces entropy and dictates the direction of spontaneous change, helping predict which phase transformations or diffusion processes will occur naturally.

The Third Law sets the absolute reference point for entropy, describing how materials behave as they approach perfect order near absolute zero — crucial for low-temperature and quantum materials research.

Together, these fundamental laws empower materials scientists to:

Predict and analyze the thermodynamic stability and equilibrium of material phases, ensuring the correct structures form under specific temperature and pressure conditions.

Regulate and optimize energy flow and thermal efficiency in processes such as heat treatment, alloy solidification, and energy-conversion devices.

Identify and quantify the thermodynamic driving forces governing atomic diffusion, chemical reactions, and phase transformations in solids.

Engineer advanced materials with customized thermal, mechanical, and electronic properties, aligning their performance with desired functional and industrial requirements.

By mastering the laws of thermodynamics, students and researchers develop the scientific insight to interlink energy, structure, and functionality — the three foundational pillars that govern the design, behavior, and performance of advanced materials in modern science and engineering.

Dr. Rolly Verma

If you notice any inaccuracies or have constructive suggestions to improve the content, I warmly welcome your feedback. It helps maintain the quality and clarity of this educational resource. You can reach me at: advancematerialslab27@gmail.com

Explore More from Advance Materials Lab

If you found this guide on Thermodynamics in Materials Science helpful, you might also enjoy reading these related articles:

🧠 How to Stay Organized in Research Life — Practical tips to manage experiments, publications, and research deadlines efficiently.

⚡ Dirac Plasmon Polaritons in 2D Metamaterials — Discover how 2D quantum systems redefine light–matter interactions.

🔬 History of Piezoelectricity — A fascinating journey through the discovery and development of piezoelectric materials.

🧩 Ferroelectrics Tutorials & Research Guides — Deepen your understanding of polarization, domain dynamics, and hysteresis.

⚙️ Radiant Precision Ferroelectric Tester — Learn how advanced instrumentation supports ferroelectric and dielectric measurements.