The Untold History of Piezoelectricity: From Accidental Discoveries to Technological Power

When most students hear about piezoelectricity, the story begins with Pierre and Jacques Curie in 1880, gently pressing quartz crystals and observing electric charges on their surfaces. While this discovery was groundbreaking, the real history of piezoelectricity is far more profound — full of accidental insights, forgotten materials, overlooked scientists, and even secret wartime projects.

In this blog, we go beyond the textbook version to uncover the untold history of piezoelectricity — showing how chance discoveries, hidden experiments, and global events shaped a technology that powers everything from sonar and sensors to modern smart devices.

Table of Contents

Accidental Beginnings: The Curie Brothers and Pyroelectricity

The Curie brothers did not set out to discover piezoelectricity at all. Their real interest was in pyroelectricity — the generation of electric charges in crystals due to heating. During these studies, they wondered if mechanical pressure might have a similar effect and stumbled upon the piezoelectric phenomenon.

A year later, Gabriel Lippmann, working purely on thermodynamics, projected that the electricity also had the potential to induce strain in crystals. — the “converse effect.” Remarkably, the Curies confirmed this projection, making piezoelectricity one of the earliest examples where theory and experiment met in perfect harmony.

A “Scientific Curiosity” Forgotten

Despite the brilliance of its discovery, piezoelectricity lived for decades in the shadow of indifference. From 1880 through the early 20th century, it remained an effect to mineralogists and theoretical physicists only but offered little to engineers. Researchers carefully measured charge responses in quartz, tourmaline, and Rochelle salt, adding to the catalogue of crystal properties, yet no one could imagine a device that would benefit from this strange coupling of stress and electricity. At the time, electrical technology was dominated by metals, magnetism, and vacuum tubes, leaving little room for exotic crystalline effects.

In fact, early physics textbooks of the 1890s and 1900s often relegated piezoelectricity to a few passing lines, describing it as “a beautiful demonstration of crystal asymmetry” but not much more.

For nearly thirty years, piezoelectricity was referenced in papers and classrooms as an elegant but impractical curiosity — a footnote in crystallography rather than a force shaping technology. It was only during the World War I when the urgency of global conflict demanded entirely new ways of “seeing” and “sensing” the environment that piezoelectricity stepped out of obscurity and into the realm of real-world applications. The French physicist Paul Langevin best known for his pioneering work in paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and ultrasonics secretly harnessed piezoelectric quartz to design an underwater sonar system for detecting submarines. Langevin created a way to locate submarines — a critical innovation at a time when submarine warfare threatened Allied shipping. Although the technology was not perfected before the war’s end, this marked the first major application of piezoelectricity and set the stage for future military and civilian uses.

The Forgotten Rival: Rochelle Salt

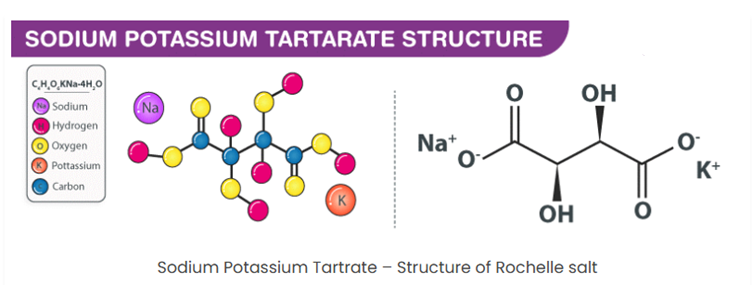

In the early decades of the 20th century, quartz may have been the scientific symbol of piezoelectricity, but it was not the only material under investigation. Rochelle salt (sodium potassium tartrate), a transparent and easily cleavable crystal first discovered in the 17th century, emerged as an unlikely hero. Unlike quartz, its piezoelectric response was extraordinarily strong, making it remarkably sensitive to mechanical vibrations. This sensitivity briefly earned Rochelle salt a place in the technological landscape, where it was used in experimental microphones, phonograph pickups, and even some early electroacoustic devices. However, its fragility and tendency to dissolve in water made it unsuitable for long-term applications. By the 1930s, as engineers sought piezoelectric materials capable of surviving real-world conditions, Rochelle salt began to fade from the scene. It was gradually overshadowed first by the rugged reliability of quartz and later by the advent of ferroelectric ceramics such as barium titanate and lead zirconate titanate (PZT), which combined strong piezoelectric responses with durability and ease of manufacture.

Rochelle Salt and the Birth of Ferroelectricity

Interestingly, Rochelle salt did not simply vanish into obscurity after its decline in piezoelectric applications. In the 1930s, it became the first crystal in which scientists observed ferroelectricity — the phenomenon where a material possesses a spontaneous electric polarization that can be reversed by an external electric field. This discovery opened an entirely new chapter in condensed matter physics, laying the groundwork for the study of ferroelectric materials such as barium titanate and PZT. In this sense, Rochelle salt acted as a bridge between the early curiosity-driven era of piezoelectricity and the technologically transformative era of ferroelectric research.

Japan’s Hidden Legacy in Piezoelectric Technology

It is believed that Japan, ahead of its time, had already embarked on industrial-scale production of piezoelectric devices in the 1930s — an era when the West still viewed them as mere curiosities. Historical reports from Japanese patent archives and engineering journals reveal that firms such as Nihon Onkyo and Tokyo Denki were experimenting with Rochelle salt and quartz-based devices for microphones, phonograph pickups, and early ultrasonic transducers during this period. By the late 1930s, Japanese naval laboratories were already adapting piezoelectric quartz resonators for sonar and underwater acoustic communication, a decade before piezoelectric ceramics like barium titanate (BaTiO₃) were discovered.

After World War II, Japan’s wartime investment in piezoelectric technology provided a strong foundation for rapid postwar development. Japanese scientists at institutions like the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN) and Tokyo Institute of Technology quickly shifted to research on ferroelectric ceramics, particularly BaTiO₃, which had been independently discovered in both the U.S. and Japan in the 1940s. By the 1950s, Japanese companies such as Matsushita (Panasonic) and Murata Manufacturing were mass-producing ceramic capacitors, resonators, and filters, outpacing Western rivals in miniaturization and manufacturing efficiency. This early initiative explains why Japan is powerful leader in piezoelectric technologies today. Even in the 21st century, Japanese companies — Murata, TDK, Kyocera, and NEC — remain global leaders in the production of piezoelectric ceramics and devices.

The Discovery of Barium Titanate (BaTiO₃)

In the 1940s, scientists discovered barium titanate (BaTiO₃), which was one of the first ceramics to show strong ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties. This discovery happened independently in both the United States and Japan, mainly during wartime research. Because of its importance in developing radar and sonar, much of the research was kept secret at the time. After the war, BaTiO₃ became very important in technology. It was widely used in capacitors, sensors, and transducers, and it marked the beginning of modern piezoelectric ceramics.

Cold War Competition and the Rise of PZT

Right after World War II, historians often date the Cold War from 1947, piezoelectric materials became critical for warfare systems. Therefore, in the early 1950s, researchers in both the United States and Japan began experimenting to find the new piezoelectric materials that outperformed the existing crystals like quartz or BaTiO₃.

In the year 1952–1954, the discovery of new ceramic material, lead zirconate titanate (PZT) with extraordinary properties came into existence fuelling rapid advancements piezoelectric technology. The first systematic reports on PZT solid solutions came from Japanese researchers led by Yasuhiro Jaffe (working in collaboration with Bell Telephone Laboratories, USA) and independent Japanese groups (notably at Tokyo Institute of Technology).

Further, in 1969, a group of Japanese researchers led by Hideki Kawai at the Tokyo Institute of Technology discovered that when PVDF films (a piezoelectric polymer) were stretched and electrically poled, they exhibited remarkably strong piezoelectric and pyroelectric effects. PVDF was the first polymer shown to have piezoelectric properties comparable to ceramics like PZT — but with advantages of flexibility, light weight, and ease of processing. This opened the door to flexible sensors, microphones, energy harvesters, and biomedical devices. However, PVDF material was already discovered as a chemical polymer in the 1940s by DuPont, a French chemist who emigrated to America in the 19th century.

Final Takeaway

The history of piezoelectricity is not a straight path of discovery and innovation. It is a story of accidents, forgotten materials, invisible contributors, and classified military research. From its accidental beginnings with the Curie brothers to its critical role in wartime technologies and its surprising rediscovery in polymers, piezoelectricity’s history is as asymmetric and fascinating as the crystals that make it possible.

References:

Y. Jaffe, R. S. Roth, and S. Marzullo published their landmark paper “Piezoelectric Properties of Lead Zirconate–Lead Titanate Solid-Solution Ceramics” in 1954 (Journal of Applied Physics, Vol. 25, p. 809).

Kawai’s paper: “The Piezoelectricity of Poly (vinylidene fluoride)”, published in Japanese Journal of Applied Physics, 1969.

Dr. Rolly Verma

Explore More Articles on AdvanceMaterialsLab.com

Continue building your understanding of advanced materials through our specialized research tutorials and student-friendly guides.

If you notice any inaccuracies or have constructive suggestions to improve the content, I warmly welcome your feedback. It helps maintain the quality and clarity of this educational resource. You can reach me at: advancematerialslab27@gmail.com