Why Graphene Is the Fundamental Building Block of Carbon Nanotubes

When students first encounter carbon nanotubes, they often focus on their tube-like appearance and extraordinary properties. However, to truly understand why carbon nanotubes exist and how their properties originate, we must step back and examine something even more fundamental. That foundation is graphene.

Carbon nanotubes do not emerge from carbon atoms randomly arranging themselves into tubes. Instead, they originate from a very specific and highly stable atomic arrangement of carbon. This arrangement is graphene. In fact, every carbon nanotube can be understood as a graphene sheet that has been transformed geometrically. Without understanding graphene, carbon nanotubes remain only a fascinating shape. With graphene, they become a logical outcome of carbon chemistry and physics.

Carbon bonding as the starting point

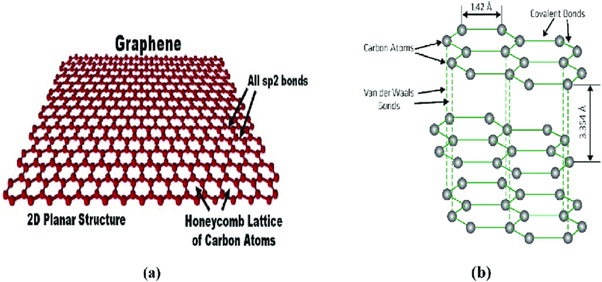

Carbon is unique among elements because of its strong tendency to bond with itself. This self-bonding capability arises from carbon’s four valence electrons, which allow it to form multiple covalent bonds in different hybridization states. In the case of graphene, carbon atoms adopt sp² hybridization. Each carbon atom forms three strong σ-bonds with neighboring carbon atoms, while the remaining electron occupies a p-orbital that participates in π-bonding.

This bonding arrangement naturally forces carbon atoms to organize themselves in a planar structure. The most energetically favorable configuration is a hexagonal lattice, where each carbon atom is connected to three others at 120-degree angles. The result is a perfectly ordered two-dimensional sheet of carbon atoms.

Understanding graphene as a material

Graphene is not simply a thin form of graphite; it is a distinct material with its own identity. It is one atom thick, meaning all carbon atoms lie in a single plane. There is no repetition in the vertical direction, and therefore no bulk thickness in the conventional sense. Because of this two-dimensional nature, graphene is often described as the most fundamental form of carbon-based materials.

Many other carbon allotropes can be traced back to graphene. Graphite is formed when many graphene sheets stack on top of one another. Fullerenes are formed when graphene sheets curve and close into spherical shapes. Carbon nanotubes, as we will see, are formed when graphene sheets roll into cylinders. From this perspective, graphene acts as the structural parent of an entire family of carbon materials.

From a flat sheet to a nanotube

Now we reach the central idea of this tutorial. Imagine holding a perfectly flat graphene sheet at the atomic level. If this sheet is rolled seamlessly so that one edge meets the opposite edge, a hollow cylindrical structure is formed. This cylinder is a carbon nanotube.No atoms are added during this transformation, and none are removed. The bonding remains sp² throughout the structure. The only change is geometric. Because the atomic connectivity is preserved, carbon nanotubes inherit many of graphene’s intrinsic properties. This is why carbon nanotubes are often described as one-dimensional graphene.

Why the rolling direction matters

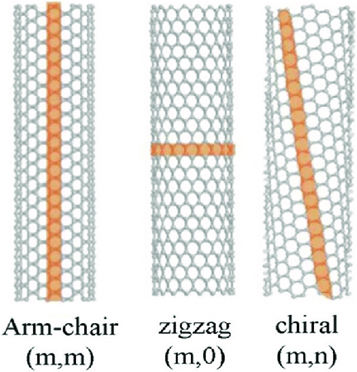

Although all carbon nanotubes originate from graphene, not all nanotubes are identical. The properties of a carbon nanotube depend strongly on how the graphene sheet is rolled. Graphene has a highly symmetric hexagonal lattice, and rolling can occur along different lattice directions.

When the rolling direction aligns along specific crystallographic orientations of graphene, different atomic arrangements appear along the circumference of the tube. This structural feature is known as chirality. Chirality determines whether a carbon nanotube behaves as a metal or as a semiconductor, even though all nanotubes are made of the same element.

Thus, the electronic diversity of carbon nanotubes originates directly from graphene’s lattice symmetry.

Why graphene prefers to become a tube

A natural question arises at this stage: if graphene is so stable, why does it roll into nanotubes at all? The answer lies in nanoscale energetics. In a finite graphene sheet, the atoms at the edges possess dangling bonds. These dangling bonds increase the system’s energy and make the structure less stable.

By rolling into a nanotube, graphene eliminates these exposed edges. The structure becomes closed and continuous, significantly reducing surface energy. At the nanoscale, this energy reduction is sufficient to drive tube formation during synthesis processes such as chemical vapor deposition. In simple terms, carbon nanotubes form because they are energetically more favorable than open-ended graphene fragments.

Electronic transformation from graphene to CNTs

Graphene is famous for its exceptional electronic behavior, where electrons move as if they are massless particles. When graphene is rolled into a nanotube, electron motion becomes confined around the circumference of the tube. This confinement leads to quantization of energy levels and modifies the electronic band structure.

As a result, carbon nanotubes can exhibit metallic or semiconducting behavior depending on their diameter and chirality. Importantly, these electronic properties are not new phenomena introduced by nanotubes; they are direct consequences of graphene’s electronic structure under geometric confinement.

Mechanical strength inherited from graphene

Graphene is one of the strongest materials ever discovered due to its robust sp² carbon–carbon bonds. When graphene is transformed into a nanotube, this strength is preserved. At the same time, the cylindrical geometry provides flexibility, allowing nanotubes to bend without breaking.

This combination of strength and flexibility explains why carbon nanotubes possess extraordinary mechanical properties and why they are studied extensively for reinforcement, nanoelectromechanical systems, and advanced composites.

Why this concept is essential for students

For students and researchers, recognizing graphene as the building block of carbon nanotubes brings clarity. Growth mechanisms, transmission electron microscopy images, electronic band diagrams, and mechanical models all become easier to understand once CNTs are viewed as transformed graphene sheets. Instead of memorizing properties, students can derive them logically from graphene’s structure.

Final takeaway

Carbon nanotubes are not mysterious or accidental structures. They are the natural outcome of graphene’s atomic arrangement, bonding, and energetic preferences. Every nanotube begins as graphene, and every remarkable property of carbon nanotubes can be traced back to graphene’s hexagonal lattice and sp² bonding network.

If you are new to this topic, we recommend starting with

Carbon Nanotubes – Part 1: Discovery and Growth of Carbon Nanotubes

👉 Read here:

References:

Iijima, S. (1991). Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature, 354, 56–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/354056a0

Saito, R., Fujita, M., Dresselhaus, G., & Dresselhaus, M. S. (1992). Electronic structure of graphene tubules based on C₆₀. Physical Review B, 46(3), 1804–1811. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.46.1804

Dresselhaus, M. S., Dresselhaus, G., & Eklund, P. C. (1996). Science of fullerenes and carbon nanotubes. San Diego: Academic Press.

Castro Neto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S., & Geim, A. K. (2009). The electronic properties of graphene. Reviews of Modern Physics, 81(1), 109–162. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.81.109

Wallace, P. R. (1947). The band theory of graphite. Physical Review, 71(9), 622–634. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.71.622

Saito, R., Dresselhaus, G., & Dresselhaus, M. S. (1998). Physical properties of carbon nanotubes. London: Imperial College Press.

Dekker, C. (1999). Carbon nanotubes as molecular quantum wires. Physics Today, 52(5), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.882658

Novoselov, K. S., Geim, A. K., Morozov, S. V., Jiang, D., Zhang, Y., Dubonos, S. V., Grigorieva, I. V., & Firsov, A. A. (2004). Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science, 306(5696), 666–669. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1102896

Jorio, A., Dresselhaus, G., & Dresselhaus, M. S. (2008). Carbon nanotubes: Advanced topics in the synthesis, structure, properties and applications. Berlin: Springer.

Dr. Rolly Verma

Explore More from Advance Materials Lab

Continue expanding your understanding of material behavior through our specialized resources on ferroelectrics and phase transitions. Each guide is designed for research scholars and advanced learners seeking clarity, precision, and depth in the field of materials science and nanotechnology.

🔗 Recommended Reads and Resources:

Ferroelectrics Tutorials and Research Guides — Comprehensive tutorials covering polarization, hysteresis, and ferroelectric device characterization.

Workshops on Ferroelectrics (2025–2027) — Upcoming training sessions and research-oriented workshops for hands-on learning.

Glossary — Ferroelectrics and Phase Transitions — Concise explanations of key terminologies to support your study and research work.

- Material Science & Ceramics — A comprehensive guide to nanoceramics, electroceramics and thermodynamics.

If you notice any inaccuracies or have constructive suggestions to improve the content, I warmly welcome your feedback. It helps maintain the quality and clarity of this educational resource. You can reach me at: advancematerialslab27@gmail.com